Abington Enslavers Separated Black and Native Families

February 19, 2024

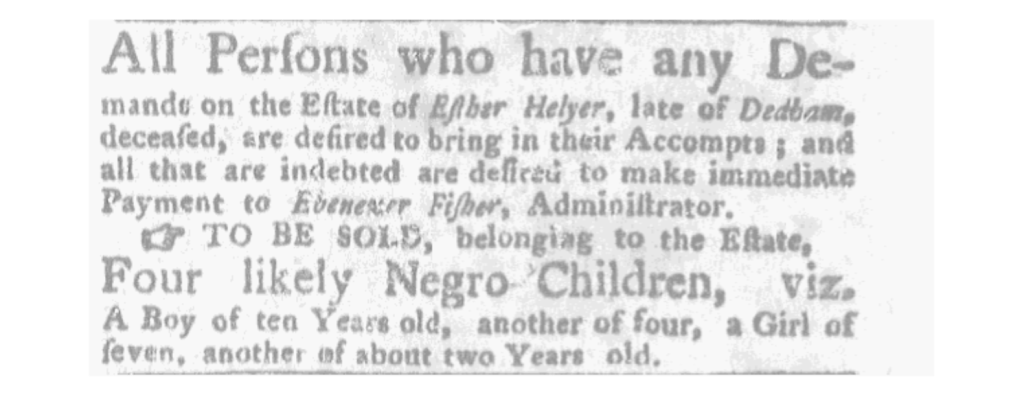

Family separation was a standard tool abused by slaveholders to subjugate Black and native people. At any given time, enslavers could sell away enslaved family members. Or, in the words of the Rev. Jeremy Belknap, they could give Black children “away like puppies.”

Enslavers inflicted this trauma on children and parents alike. In her poem To the Right Honorable William, Earl of Dartmouth, the American genius Phillis Wheatley Peters captured the essential expression of separation pain. Wheatley Peters, who arrived in Boston as a kidnapped, malnourished, barely-clothed, abused seven-year-old girl, revealed herself as a teenage prodigy and became the first African author published in English. In 1773, she lamented:

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

– Phillis Wheatley Peters, 1773

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Modern writers extoll Phillis’ exceptionality, and we cannot overstate her excellence. However, Phillis’ kidnapping commonizes the poet with Africans in every corner of the eighteenth-century Atlantic World. Enslavers replicated her violent dislocation countless times in West Africa, the West Indies, Virginia, Boston—and Abington.

Abington resident Priscilla’s parents are, like Phillis’, unknown. And like Wheatley Peters, the first record of Priscilla is as an enslaved child.

Captain John Burrill identified Priscilla in his will as a “garl” whom he bequeathed to his wife Mary. Burrill’s body and 1754 headstone lie at Maplewood Cemetery on Webster Street at the Hanover town line. The marker is noteworthy as “Rockland’s oldest headstone;” unknown, though, is Priscilla’s final resting place, or the final resting place of Dina–another woman enslaved by Burrill–or the final resting place of dozens of African and native people enslaved in the Old Abington towns that included Rockland and Whitman.

Our second and final witness point is when Mary Burrill manumitted her “negro woman named Priscilla” in her 1771 will. There are no “benevolent enslavers,” and Mary Burrill wasn’t “kind” to “free her slave” upon her death. The Burrills stole Priscilla’s childhood and young adult life, and it was unlikely they formally educated her. Upon her freedom, she did not receive back wages for her labor or any pension; she only received her “clothing and sundry things.” Imagine working uncompensated for a quarter century and starting a “free” life with only the clothes on your back.

Priscilla’s life is visible only in scant details refracted through documents designed to protect and transfer property. She did not leave an artistic corpus to examine, nor do we have humanizing records of Priscilla’s baptism, marriage, or death. We must remember Priscilla, then, through our imaginations and the art of another Massachusetts child snatched away from her parents, Phillis Wheatley Peters.

More:

SUBSCRIBE TO MY NEWSLETTER: https://elevennames.substack.com/

Copyright Wayne Tucker 2024. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Leave a comment