UNEARTHING SLAVERY IN ABINGTON

How does slavery tie into the founding of Abington, Mass? And what does the town’s first minister have to do with a forgotten woodland gravesite that holds a Revolutionary War veteran and Wampanoag royalty?

by Wayne Tucker | September 28, 2021 | @elevennames | wayne.tucker@gmail.com | HOME

If you grew up in Abington or her constituent towns of Whitman and Rockland, you grew up believing that slavery barely existed in Massachusetts and that you needed to travel to former confederate states to visit lands once farmed by enslaved people; this can no longer be the case.

There is an invisible yet well-documented history of slavery in Abington. Colonial Abington’s incorporation was contingent upon the arrival of prolific enslaver Reverend Samuel Brown. Native people were enslaved in Abington alongside Black bondspeople. The town had at least two working farms made viable by slave labor and the archives pinpoint the locations of these farms: the Brown farm site lies on one of the heaviest-traveled thoroughfares in town and the Torrey farm site lies on an idyllic street that exudes country charm.

Slavery existed in Massachusetts for a longer period than it did in English-speaking Georgia. Although the exact dates are hard to pin down, historians note slavery in Massachusetts is roughly bookended between the arrival of the ship Desire which trafficked enslaved Africans to Massachusetts in 1638 and a 1783 Massachusetts court decision that abolished slavery by statute, if not yet in practice. At one point, 25% of the white families in Boston were slaveholders1, and enslaved people comprised 12%-14% of the population2. Across New England, the percent of the population of people that were enslaved averaged about 2% to 4%, but varied by location3.

Two Ministers

Two more things readers need to know is: a.) to incorporate as a new town in colonial Massachusetts, the town needed to hire and support a minister and b.) like many frontier settlements across time, people buried their dead in the family plot on family property.

Across Abington, there was the Nash family tomb, the Cobb family burying ground, the Hunt family tomb…we know of eleven such cemeteries that have seemingly vanished, or, like the Richards family burial ground, remain in a hidden corner of Abington adjacent to Ames Nowell State Park. This digital research project unravels the curious story of why one such gravesite exists and how its inhabitants came to rest there.

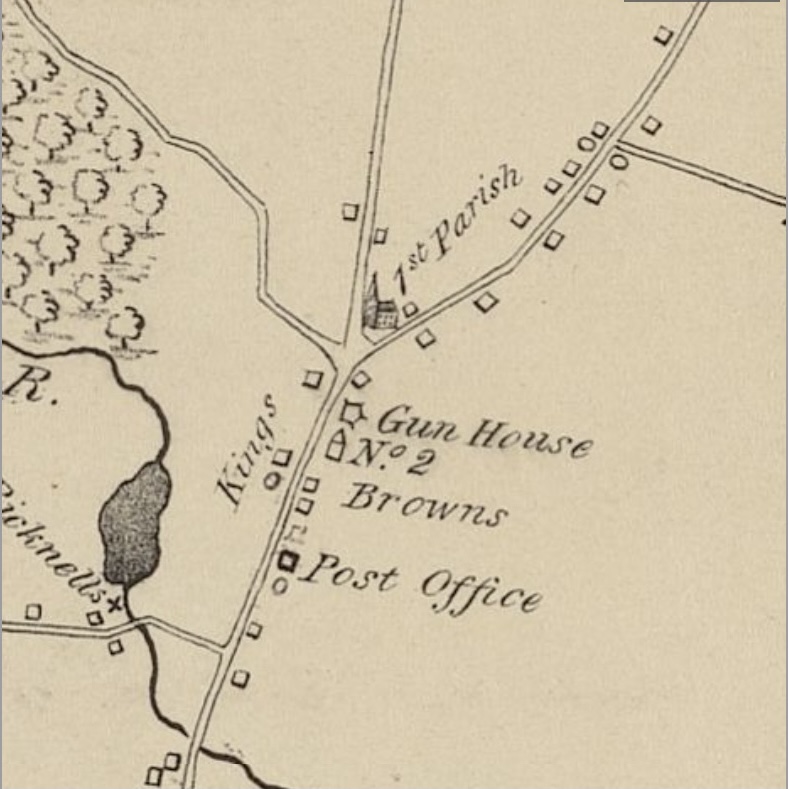

Today, the “Old Church Burying Ground” land is now occupied by Route 18 Auto Body, as 325 Washington Street was the site of Abington’s original church. The town is situated 20 miles south of Boston and between the 1670s and the 1710s the population in the area grew because the turnpike connecting Boston and Plymouth ran through the settlement; the site of the first meeting house marked the halfway point between the two colonies. When Abington petitioned Governor Dudley to become a town, they were short on the requirement of having hired a minister until Rev. Samuel Brown arrived in 1712.

Rev. Brown enslaved many people, including the children born on his property. Brown’s parsonage was close to the church and records indicate that the minister was deeded a 60-acre farm as an incentive to leave Newbury for Abington. The house at 303 Washington Street was built 40 years after Brown’s 1749 death by great-grandson Lt. Samuel Brown. It still stands today on one of the parcels subdivided from Samuel Brown’s original estate and the Brown family continually passed this property down through generations into the twentieth century.

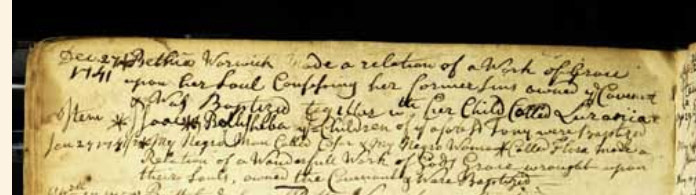

The vicinity surrounding today’s Route 18 Auto Body would have been the center of life for enslaved people Besse, Tony, Cuff, Cesar, Flora, Ezra, David, and Amos. Not only was it the place where they labored, slept, and cared for themselves, but at least five of the enslaved people were baptized and/or became members of the church; we know this because we can examine Brown’s diary and see notes written in his own hand with digitized records from Boston’s Congregational Library. The reverend’s son Woodbridge Brown was admitted to the church on October 3, 1742, the same day Brown notes the admission of “my Negro Man Tony.” Below we see a couple, the enslaved Cesar and Flora, being baptized.

Congregational Library & Archives, Boston, MA

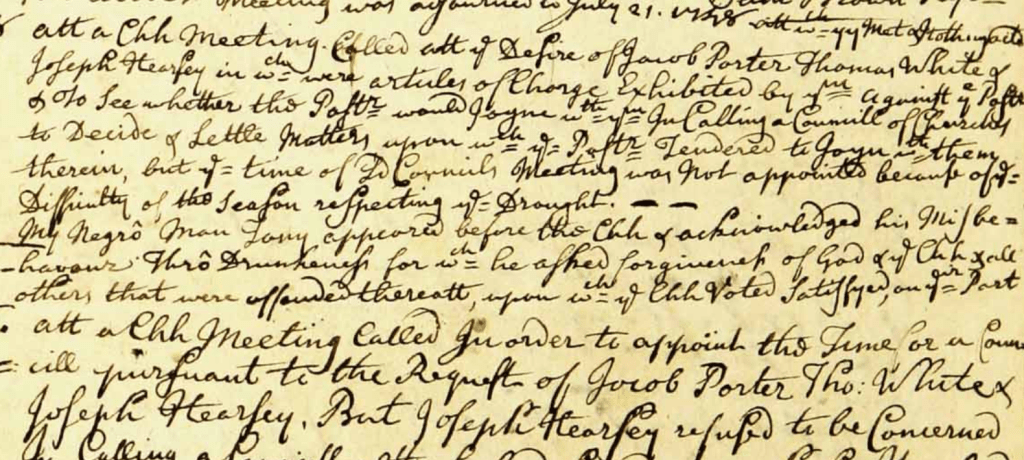

Being the only meetinghouse in town, these enslaved people would have attended church alongside every other resident of Abington; they would have been seen and people would have known who they were and to whom they belonged. White Abingtonians witnessed their baptisms and confirmations, and in 1748 parishioners witnessed the enslaved man Tony apologizing to the congregation for his drunkenness. These were not invisible lives lived in distant fields. The people held in bond by the Rev. Brown were neighbors, albeit of an enslaved class, to the white population of Abington.

Congregational Library & Archives, Boston, MA

Benjamin Hobart references Rev. Brown’s enslaved people in his indispensable “History of the Town of Abington” (1866) where he notes that these people entered into the bondage of Josiah Torrey. Samuel Brown died in 1749 and his widow Mary married “Old Squire Torrey” as Josiah was called, and the new couple took up residence at the Abington farm of Mary’s father, Matthew Pratt. Amusingly, Torrey, a former minister himself, had a taste for clergy widows: not only was his first wife, who was 51 years old and 20 years his senior, the wife of the town’s first minister, but his second wife, also named Mary, was the widow of the second minister, Ezekiel Dodge. Through the consolidation of historic burial grounds, this intertwined family of ministry and slavery rest eternally together in the Minister’s Corner of Abington’s Mount Vernon Cemetery.

Besse Goold was born into slavery on Reverend Brown’s farm in 1734 to the abovesaid Cesar and Flora; from whence the Goold surname came, it is unknown. Besse would in turn bear a child in 1759 named Brister Goold while living in bondage at the Torrey farm.

A search of probate file archives yields Josiah Torrey’s original 1783 will, said to be in his handwriting. Directly under a £3 donation to the Congregational church, he returns Besse her stolen freedom. Below that, we see Torrey returns the freedom of Brister upon his 25th birthday, which fell a year later in December of 1784. Surprisingly, Torrey further bequeaths Brister 15 acres of land.

TRANSCRPT: Item. I give unto the Church of Christ in Abington three pounds in Money to be Laid our in Vessels for the Sacramental Table.

Item. I let free and give my Negro Woman Besse Goold her freedom and Liberty for ever and all her things and especially the Bed and bedding which she uses and Claims I give to her for her own Property for ever.

Item. I give unto my Man Brister Goold after he may arrive to the age of Twenty-five years his freedom and Liberty for ever. Also I give unto the Said Brister Goold Fifteen Acres of Land at the Easterly end of the Lot that is called Lovells Lot, and to extend far westerly as to make Fifteen Acres to him and his heirs for ever, but under this restriction…that he shall not Dispose nor alter the Property of it without the advice and consent of my aforesaid Cousin Josiah Torrey upon any Consideration whatever, lest he should be beguiled and Deceived. Likewise, I give unto the said Brister Goold Liberty to cut Timber for a Small frame for a House and Barn, and Logs for Boards and Shingles to build and finish them where my Said Kinsman Josiah Torrey may think most proper and convenient, and without Waste and Damage that the said Brister may be under circumstances to assist and help provide for his Mother. Also I give unto said Brister Goold that Bed and Bedding which is called his, and which he lodges on. Moreover, I give unto the said Brister Gould a Small Gun.

Item. I give unto my other Negro Woman Cate her freedom and Liberty for ever.

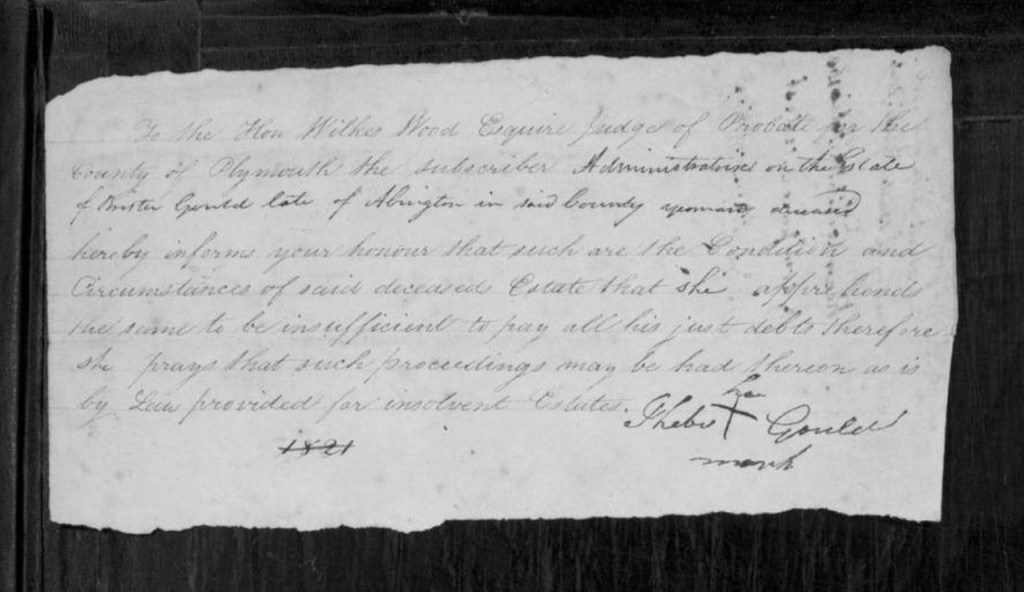

Abington’s vital records show that Brister died in 1823, aged 63, where he is categorized as “a person of color;” luckily, his will survives in the archive, too. We see that he still owned property left to him by Torrey and that his widow Phebe is executrix of his estate. Phebe’s signature is marked with an ‘X’ indicating she was presumably illiterate in English; therefore we are left wondering how fairly and honestly the probate court and Phebe’s neighbors treated the widow, as Brister’s estate is declared insolvent and Phebe appears on the pauper rolls in her hometown Middleborough the following year. But the illiterate “pauper” widow’s extraordinary backstory unlocks historical secrets that few locals know about.

Phebe Wamsley and Brister Gould

Phebe’s life is not attested solely through probate transactions and pauper rolls. Abington’s vital records report that she married Brister in Middleborough in 1797; unusually for nonwhite people, though, neither the bride nor groom’s race is mentioned and the union does not appear under the segregated “Negro” section of the town’s marriage records. Records also indicate seven children born to the couple, and, as it turns out, one daughter, Zerviah Gould Mitchell, had profile in her day. An activist and publisher, Mitchell’s work is described in a 2018 press release from Plymouth’s Pilgrim Hall as “pioneering” and noted that she was “an advocate for the rights of Native Americans who sought to preserve Native histories.”

In Zerviah’s Indian history, biography and genealogy book, the entry for her mother reads:

Phebe Wamsley, daughter of Wamsley and Lydia Tuspaquin, was born Feb. 26, 1770. She married 1st, Nov. 27, 1791, Silas Rosier, an Indian of the Marshpee tribe, who served as private soldier in the patriot army of the war of American Revolution, entering that service at the commencement of the conflict, and serving until its close. He died at sea, and his widow married 2d, March 4, 1797, Brister Gould, he for a time served as teamster to the patriot army in our revolutionary war. He was drowned at a place called Hawkley, in East Weymouth, Mass., Aug. 28, 1823. She died Aug. 16, 1839.

Peirce, E. Weaver., Mitchell, Z. Gould. (1878). Indian history, biography and genealogy: pertaining to the good sachem Massasoit of the Wampanoag tribe, and his descendants. With an appendix. North Abington, Mass.: Z. G. Mitchell.

Zerviah’s book also recounts that Phebe’s mother Lydia Tuspaquin was “the chief amanuensis [interpreter, historian] of her people” and “[w]hile she was residing at Petersham, a bear came one night and took a small pig, Lydia resolutely rushed out, musket in hand, shot the bear and saved the pig before bruin had time to kill it.” This book goes on to establish Phebe as a descendant of Massasoit (Sachem Ousamequin), who was the Wampanoag leader at the pivotal time of the Pilgrims’ arrival at Plymouth; Tuspaquin, known as the Black Sachem for his tenacious resistance in King Philip’s War and who was tried and executed by the English; and John Sassamon (Wasassman) who was one of John Eliot’s star pupils and whose murder trial was an accelerant to the explosive build-up of to King Philip’s War. These are three titanic Wampanoag names in colonial Massachusetts history.

This deserves a recap: Phebe, the woman who marked ‘X’ on Brister Goold’s probate documents, descends from Wampanoag noble blood. Her mother played a key tribal role and her male ancestors fought English colonizers in King Philip’s War, while her two husbands served in the fight against the British during the Revolution, both later drowning. Then, one of her daughters with Brister became an indigenous rights trailblazer. Astounding stuff.

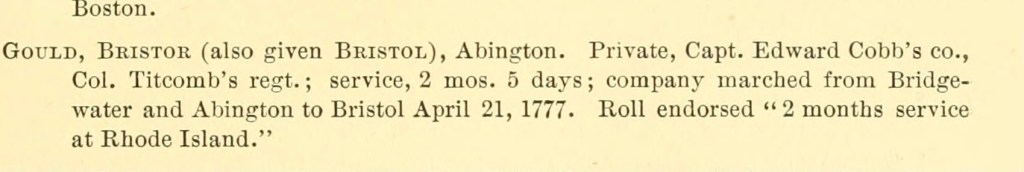

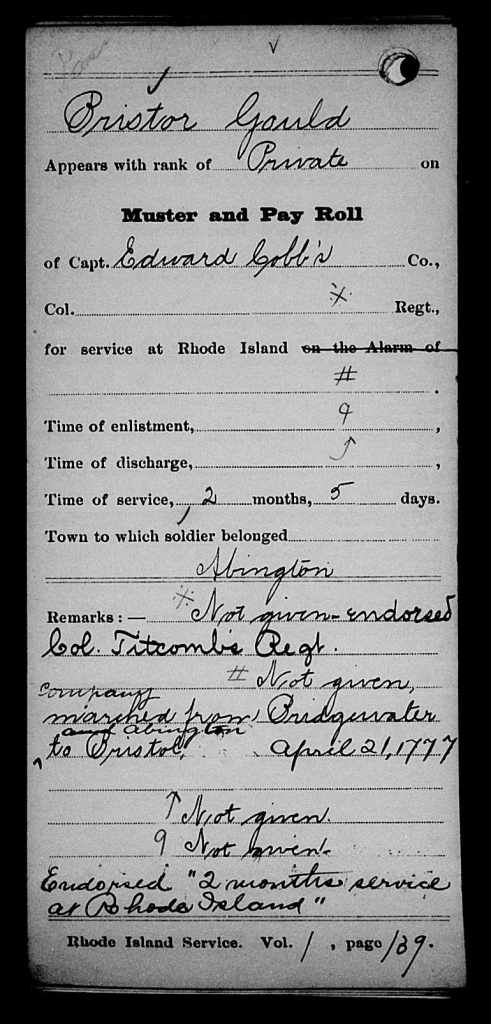

What, then, of Brister and his purported Revolutionary War service as a teamster? Sure enough, in the Daughters of the American Revolution “Forgotten Patriot” research guide (p.133 #129), we find Brister Gould’s name in the Massachusetts section and it notes that he was formerly enslaved by Squire Torey and married to Phebe. Additionally, digging into Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (henceforth MSS), we see Brister served two months in Capt. Cobb’s company in 1777. Having a December birthday, this would mean Brister was 17 years old at the time of his service. Muster and Pay Roll stubs appear for Brister in 1781 and 1782 as well.

Josiah Torrey died in 1783 and Torrey’s conditions for Brister’s emancipation would not be met until 1784; Brister was enslaved while serving the Patriot army at age 17. How, then, was Brister conscripted into military service? Was Old Squire Torrey compelled by local authorities to send his enslaved man? Did Torrey feel an obligation to materially contribute to the war efforts via Brister’s forced service? Did Torrey cut a deal with the local militia to receive Brister’s pay?

Records are sparse, but we do know this isn’t the only time Torrey sent an enslaved man to fight on Abington’s behalf. The Dyer Memorial Library & Archives maintains an honor roll of Abington veterans; listed under the French and Indian War heading we find “ *Micah a slave of Josiah Torrey, Esq.” The asterisk indicates killed in action. Furthermore, enslaved men Cuff and Cuff Jr., surname of Rosaria/Rossier, whose last names are spelled–no exaggeration–ten different ways, are reported both a.) in vital records as being enslaved by Torrey and b.) in MSS as having served in the war. Hobart further notes that Cuff ‘Rozarer’ “died in service” during the Revolution and it is unclear if he is referring to Senior or Junior. [UPDATE: Read more about Cuff here.]

Torrey sent at least four enslaved men to war, with two meeting their death. We also know from Benjamin Hobart that, through oral tradition, Torrey was known to whip Cuff Senior and keep him in an iron neck brace with a loop for a chain. It would be impossible to argue any enslaver was benign let alone benevolent, and evidence suggests Torrey fits the “slave master” stereotype. But why, upon death, would a man of cruelty instruct his estate to emancipate Brister and his mother and grant him 15 acres?

Many enslaved people owed their emancipation directly to Revolutionary War service. The Treaty of Paris that officially ended the war was signed in September 1783, the same month that Torrey died. So, does this story end poetically with a gesture from the remorseful former minister, a deathbed change of heart based upon Brister’s war service, and the symmetry of the United States and an enslaved Black man gaining independence at the same time? Perhaps not.

Something else happened in 1783. Earlier that year, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court handed down its ruling in Commonwealth v. Jennison, the last of the 3 trials in the Quock Walker case. In 1781, enslaved Worcester County man Quock Walker sued his brutal enslaver, Nathaniel Jennison, both to recover damages and to reclaim his freedom. Walker won his civil suit, and in 1783 the Massachusetts Attorney General brought criminal charges against Jennison. He was convicted, and in this conviction, the jury affirmed Judge William Cushing’s jury instructions that repeat “all men are born free and equal” from the Constitution of Massachusetts and “[i]n short…slavery is in my judgment as effectively abolished as it can be by the granting of rights and privileges wholly incompatible and repugnant to its existence. The court are therefore fully of the opinion that perpetual servitude can no longer be tolerated in our government.”

A victory to be sure, but there was no instance where the enslaved people of Massachusetts laid down their tools en masse and walked off of their enslavers’ properties. The Quock Walker case itself was the last in a series of Massachusetts court cases brought by enslaved people. Furthermore, as scholar Jared Hardesty points out, slaveholders were reading tea leaves and did not want to lose capital. Subsequently, they trafficked approximately one thousand enslaved people out of Massachusetts to other colonies from 1760 to 17904. Even if news of the nail-in-the-coffin Quock Walker case had not reached Torrey, it was clear in 1783 which way the wind was blowing and the Harvard-educated Justice of the Peace would have been capable of gauging this.

Professor Ben Railton remarks of the post-Quock Walker time that “[w]ithin a decade, pressured by both the court decisions and their communities, Massachusetts slave owners voluntarily freed their slaves, often by changing the arrangements to those of wage labor.” By revisiting the instructions from Torrey’s will, we see that Brister must only conduct business with the “advice and consent” of Torrey’s cousin/nephew, also named Josiah, and it’s reasonable to read this instruction as a device intended to maintain control over Brister’s labor. In other words, are we to believe that under the supervision and surveillance of the junior Josiah Torrey that Brister was able to fully exploit his property and was given fair prices for its yield and fair wages for his labor? If Senior Torrey believed that Junior’s guidance was so valuable as to prevent Brister from being “beguiled and swindled,” then why was Phebe trying to sell ancestral property in Fall River in 1817, insolvent in 1823, and in the pauper rolls a year after Brister’s death? As tempting as it is for some to find redemption in Brister’s manumission, I suspect that a further investigation into the material conditions of Brister and Phebe’s post-1783 life would show a narrative arc slouching towards sharecropping and bending away from redemption.

There is one last matter to consider: that of the parentage of Brister Gould. No father is listed for Brister in the records and notably, due in no small part to his first wife being 51 years old on her wedding day, Squire Torrey died childless. Torrey would have been 39 at the time of Brister’s birth in 1759, and Besse 25. The first Mrs. Torrey would have been 60. There are several plausible explanations for Brister’s lost biological father and it is impossible to assert that Besse and Squire Torrey had a sexual encounter, but one wonders if Torrey impregnating Besse would explain why Brister is noted as “a person of colour” in his entry under the “Deaths” section of Abington’s vital records instead of “negro”? Besse Gould is listed under the segregated “Negro” heading in both the births and death sections of those records, so why doesn’t her “person of color” son with the same last name join her in either? In Middleborough’s vital records, he is recorded as “negro” upon marriage to Phebe.

Oversights occur; still, the absence of a recorded father and the nuance of Brister and his mother occupying separate racial categorizations is conspicuous and leaps off the page. Indeed, eighteenth-century racial classifications differed from modern nomenclature. For example, “mulatto” and its various spellings did refer to a person of mixed race, but frequently it represented the offspring of an African-descended person and an Indian, so there is a chance that the vital records keepers are hinting that Brister, too, descends from Indian heritage. But there’s that sizable paragraph in Squire Torrey’s will devoted to Brister’s inheritance in which Torrey refers to him as “my man Brister” and notes that Brister would “provide for his mother.” Brister’s paragraph is inserted between the manumission of two “negro” women, and the astute reader wonders why that appellation was omitted when writing about him?

What’s more, their daughter Zerviah is buried in an unmarked grave less than a quarter-mile from the prominent Minister’s Corner where the men who enslaved her father and grandmother are venerated. Two questions still burned: where the hell was Brister’s farm and where are Phebe and Brister today?

The Forgotten Woodland Gravesite

Traveling the town of Abington today, you would never know it was once home to an enslaved population, let alone an enslaved Revolutionary War veteran and his Wampanoag wife. There is a veterans’ memorial in front of the VFW, and the Island Grove park contains both the Abington Memorial Bridge dedicated to Civil War veterans and a plaque memorializing William Lloyd Garrison’s visits with local abolitionists. Revolutionary veterans’ graves in Mount Vernon Cemetery are recognized with Sons of the American Revolution medallions and Rev. Samuel Brown’s name appears on the sign at the United Church of Christ. But there is nothing in Abington indicating that Phebe and Brister ever existed. What’s more, their daughter Zerviah is buried in an unmarked grave less than a quarter-mile from the prominent Minister’s Corner where the men who enslaved her father and grandmother are venerated. Two questions still burned: where the hell was Brister’s farm and where are Phebe and Brister today?

The thought struck me that Besse and Brister’s last name of Goold eventually morphed into the modern Gould spelling. And I had noticed before that one of the names of Abington’s old family burying grounds was the Gould Family Burying Ground. My first impulse was “perhaps this was the white family from which Besse’s surname is derived?” Can I find information about who was buried here?

An internet search yields a Find A Grave page for the Gould Family Burying Ground that is maintained by local genealogical wizard and historian Mary Blauss Edwards listing 4 entries: Besse Gould, Brister Gould, Phebe ‘Squin’ Rosier Gould, and Betsey Gould Hill. Jackpot!

Moreover, Edwards’s work points me to the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS), an internet repository maintained by the Massachusetts Historical Commission that not only confirms the Find-a-Grave information, but it also unleashes a wealth of information about the lives of Brister, Phebe, and Besse compiled by local historian Martha Campbell in 1979.

That year, the Town of Abington and the Massachusetts Historic Commission (MHC) undertook an inventory of historical and culturally significant locations in the town and these recently-digitized records reside in MACRIS. As of 1979, the bodies of the 4 Gould family members were still resting in a wooded area on the property at 59 Sylvan Court in Abington, and a photo of one of the graves was affixed. “The burial place is located on high land in a quiet pine grove on the farm of what was the Gould family,” the document states. It continues by noting that the house at 59 Sylvan Court is believed to be the site of the old Brister Gould cottage. The map affixed to this record shows the gravesite is estimated to be 150 feet from the street in a wooded area, today part of the Abington conservation area called the Lincoln Street Property. 59 Sylvan Court has since been subdivided and the map indicates that this site would today lie behind 50 Sylvan Court.

Serendipitously, the outline of the Lincoln Street Property measures almost exactly 15 acres, the size of the parcel granted to Brister in Josiah Torrey’s will. I verified this using an online map-based measuring tool; if you draw a rectangle anchored at the back corner of 59 Sylvan Court, connect Sylvan Court to Lincoln Street, then measure west towards Warren Street, and use the length of Warren to square off the measurement back to Sylvan Court, you will see for yourself. Although it proves nothing and further investigation is required to assert the true original outline of the Brister Gould farm, this is a tantalizing overlap of the facts.

The question that I have obsessed over for two weeks is what is the status of the graves today? Private property on Sylvan Court abuts this site and must be respected. Access to the Lincoln Street Property from Lincoln Street looks impossible due to the thickness of the vegetation. I currently have an inquiry with the Abington Historical Commission and am waiting to hear back.

Within the Gould Family Burial Ground MHC document, we find reference to a second document relating to 287 High Street in Abington. This, as it happens, is the site of Squire Torrey’s house and farm. Digging into MHS documents, we learn several new facts. We learn that the author of this report, based on a review of the Cyrus Nash Papers at Abington’s Dyer Memorial Library & Archives, believed that Reverend Brown enslaved at least twelve people during his Abington tenure (and that’s not counting children born on his property). Eight of the twelve people were removed to Torrey’s farm after Brown’s widow remarried. For comparison, most enslaving families in Boston would have enslaved 1-2 people.

We are able to confirm that Cuff Rosaria/Rossier’s son Cuff Jr. was also enslaved by Torrey and at least one indigenous person, Violet Traveler, lived in bondage at the High Street farm. We learn that the 1810 house which stood on the property in 1979–and still stands in 2021–is believed to have incorporated the original 1729 home built on the property, meaning that it may be the oldest standing structure in Abington and that it was a witness to the enslavement of Brister, Besse, and their enslaved contemporaries. Notes on Minister’s Corner reveal that Torrey’s property stretched at least to the corner of Green Street, as that was the original location of Josiah Torrey’s tomb.

Final Words

This investigation recounts a startling story of lost graves and enslavement that starts with Abington’s incorporation and spans across three farms, two ministers, multiple generations, the Revolution, and state-wide abolition. But the story of slavery in Abington sprawls further as the Thaxters, the Nashes, and the Hobarts were also known enslavers and their slavery extended out of Abington Centre to present-day Rockland and Whitman.

A featured highlight of Abington historical lore is its active abolitionist community and visits from the likes of William Lloyd Garrison, Theodore Parker, and Lucy Stone. But to aggrandize and memorialize local abolitionism without grappling with and centering the reality of the intergenerational slavery endorsed by colonial Abington is dishonest and it amounts to stolen honor. It’s past time to tell the story of enslaved Abingtonians.

wayne.tucker@gmail.com

[at] me: @elevennames

ABOUT & BIBLIOGRRAPHY

Keywords: slavery in Massachusetts, slavery in Plymouth County, slavery in New England

SUBSCRIBE TO MY NEWSLETTER: https://elevennames.substack.com/

Copyright Wayne Tucker 2024. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Leave a comment